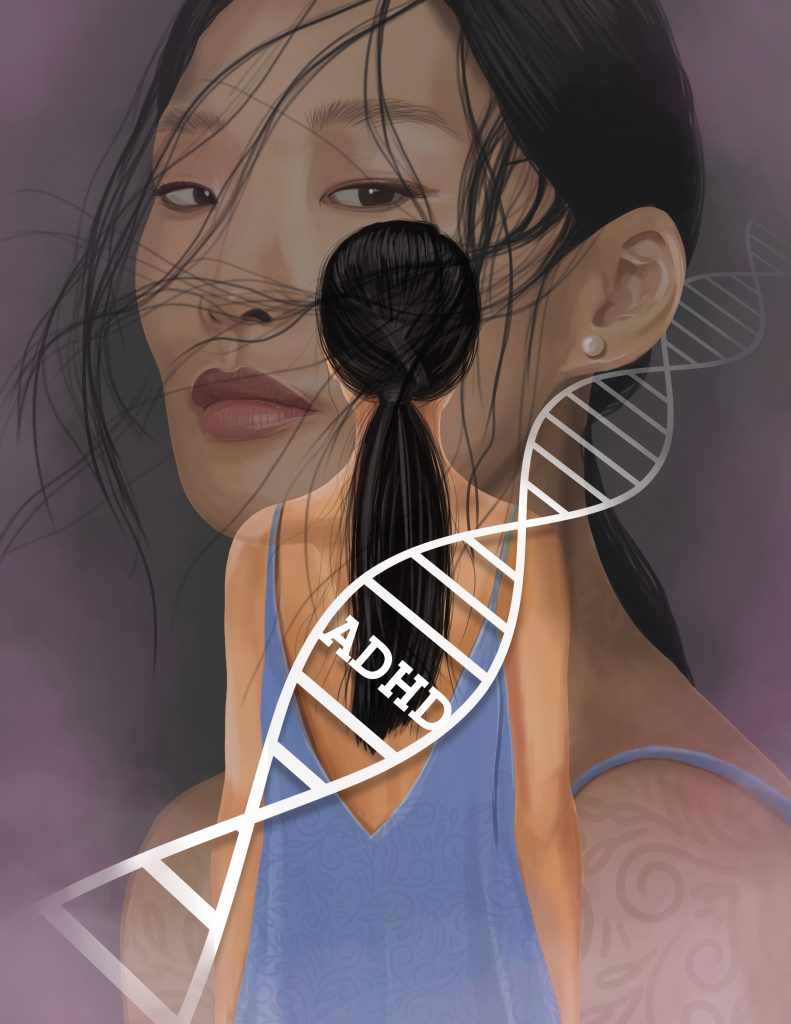

When I was a sophomore in college, I was diagnosed with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The diagnosis gave me the missing puzzle pieces needed to facilitate a deeper understanding of my life. Growing up, my parents and teachers would describe me as a little apprehensive, bright yet scatterbrained, and super-talkative. Academically, I managed as a well-mannered underachieving daydreamer, mainly getting “B’s” and “C’s”. From an early age, I tried my best to be compliant and not draw attention to myself. However, my combination type ADHD made these requests difficult. I misinterpreted symptoms like my predisposition to anger as a personality defect rather than a neurological ailment. Like many women with undiagnosed ADHD, I blamed myself and internalized my frustration. Women and girls with ADHD often go undetected, ignored, or misdiagnosed because their symptoms are misinterpreted by others as simply being talkative or ‘ditzy’ rather than symptoms of neurodiversity.

What Does ADHD Look Like – Types of ADHD

There are three general subtypes of ADHD: inattentive, hyperactive/impulsive, and combination. Inattentive type is characterized by significant attention problem symptoms, without high levels of hyperactivity and impulsiveness. The impulsive/hyperactive type refers to ADHD in individuals with excessive energy who lack impulse control. Combination type presents as high levels of hyperactivity and impulsiveness, and attention problem symptoms.

Inattentive ADHD symptoms

- Forgetful or “spacey”

- Being withdrawn

- Anxiety

- Easily distracted

- Lacking in motivation or effort

- Disorganized/overwhelmed

- Difficulty with academic achievements

- Issues focusing

- Appearing not to listen/Daydreaming

- Verbal aggression (i.e., name-calling/teasing/taunting)

Hyperactive/impulsive ADHD symptoms

- Hyperactivity (e.g., running around the room)

- Inability to sit still, even for a short amount of time

- Impulsivity or “acting out”

- Problems focusing (inattentiveness)

- Physical aggression

- Frequently interrupting activities and conversations of other people

- Talking incessantly

ADHD Is Not Only a Boy’s Phenomenon

Early studies on ADHD primarily focused on white, hyperactive boys and many researchers believed all symptoms of ADHD would subside as one got older. This set the groundwork for our societal misconception of ADHD. According to the CDC, boys are three times more likely to receive a doctor’s referral for an ADHD diagnosis and almost ten times more likely to get mediation and proper treatment compared to girls. This is not because males are more likely to have ADHD; it is due to the differences in the general presentation of symptoms between the genders.

Girls are more likely to present the inattentive type ADHD, whereas boys are more likely to display hyperactivity and impulsiveness in their condition. Adolescent girls with either inattentive or combination type usually have fewer behavioral issues and less noticeable symptoms. Symptoms in boys often lead to more disruptive behavior, which makes the disorder easier to identify. Boys with ADHD typically externalize their aggravation by ‘acting out’ or through aggression, while girls tend to internalize their frustration, blaming themselves. Girls with ADHD are more likely to suffer from anxiety, depression, or eating disorders than girls without ADHD. A late or misdiagnosis not only prevents girls from receiving the proper accommodations or services they need to succeed academically or otherwise; undiagnosed ADHD can negatively affect a girl’s self-esteem and have lasting effects on her mental well-being as well.

The Unreasonable Expectation of the “Girl Code”

Research indicates that women with ADHD often report feelings of shame when reflecting upon their adolescence. According to Patricia Quinn from the National Center for Gender Issues and ADHD, “Both girls and women who have ADHD report a sense of inadequacy as they struggle, unsuccessfully, to meet gender role expectations. These feelings may be experienced even as early as the age of 8 or 9.” ADHD experts find that adolescent girls with ADHD may work harder to hide or compensate for their symptoms. Girls may exert massive amounts of energy to control their behaviors to maintain a facade of “normalcy.” Males start to display symptoms of ADHD at a younger age than females. Usually, girls with ADHD begin to display impairment around middle school and/or on the onset of puberty. Adolescent girls experience immense pressure to be more self-controlled and socially adjusted starting around middle school.

Compared to girls without ADHD, undiagnosed girls with ADHD are more likely to struggle with social settings, school, and personal relationships. Social cues change relatively quickly from elementary to middle school, especially the unspoken social nuances of the “girl code” — how to talk, what to wear, when to comfort, when to be mean, etc. The inability to conform to the ‘girl code’ can cause girls with ADHD to become targets for mean kids. This can lead to girls with ADHD being left feeling confused and isolated from the world. Research suggests that girls and women with ADHD have a high rate of coexisting depression and anxiety. These secondary conditions are most likely to be diagnosed rather than the primary condition of ADHD.

Diagnosis in Adulthood

It has been three years since I received a proper diagnosis and began treatment for my ADHD. I had been in the dark for the majority of my life, working twice as hard to maintain a sense of normalcy. Every failure I encountered felt like hitting a brick wall, and a part of me felt broken. My diagnosis made me realize that I wasn’t broken; I just did not have all of the pieces of the puzzle. I now have a better understanding of my condition alongside the support and accommodations I need for my life to be successful. My medicine and therapy allow me to create systems that work with my ADHD, rather than against it.

References:

- “How the Gender Gap Leaves Girls and Women Undertreated for ADHD.” CHADD. Accessed August 30th, 2021. https://chadd.org/adhd-news/adhd-news-caregivers/how-the-gender-gap-leaves-girls-and-women-undertreated-for-adhd/

- “Women and Girls.” CHADD. Accessed August 29th, 2021. https://chadd.org/for-adults/women-and-girls/

- Quinn, Patricia O. “Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: Gender‐Specific issues.” Journal of clinical psychology 61, no. 5 (2005): 579-587.

- Soffer, Stephen L., Jennifer A. Mautone, and Thomas J. Power. “Understanding girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): applying research to clinical practice.” International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy 4, no. 1 (2007): 14

- Waite, Roberta. “Women with ADHD: It is an explanation, not the excuse du jour.” Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 46, no. 3 (2010): 182-196.

- Young, Susan, Nicoletta Adamo, Bryndís Björk Ásgeirsdóttir, Polly Branney, Michelle Beckett, William Colley, Sally Cubbin et al. “Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women.” BMC psychiatry 20, no. 1 (2020): 1-27.

- Quinn, Patricia O. “Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: Gender‐Specific issues.” Journal of clinical psychology 61, no. 5 (2005): 579-587.

- Soffer, Stephen L., Jennifer A. Mautone, and Thomas J. Power. “Understanding girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): applying research to clinical practice.” International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy 4, no. 1 (2007): 14